The grandfather of cryptocurrencies, Bitcoin, is notorious for not being environmentally friendly. According to a University of Cambridge study, Bitcoin is estimated to consume around 121.36 terawatt-hours (TWh) a year, which is more electricity annually than what Argentina consumes, being a country of 46 million people. This is even more than the consumption of Google, Apple, Facebook, and Microsoft combined!

At this point, it is common sense to see that Bitcoin indeed has a carbon problem. Critics are of the opinion that Bitcoin’s “utility” doesn’t justify the energy expended for it, and that the world would be better off with the traditional financial system if having a decentralized financial system meant expending gigantic amounts of energy for it. Proponents argue that Bitcoin’s inherent decentralization is worth its cost in energy consumption, and that mining is an inseparable part of Bitcoin itself.

Read on.

Proof-of-Work = Proof-of-Waste?

The main cause of Bitcoin’s mammoth energy use can be boiled down to one thing: proof-of-work mining. Before we get into it, think of blockchains as decentralized ledgers powering its underlying cryptocurrency: the Bitcoin network can be regarded as a decentralized database that anyone is free to download and maintain — Bitcoin balances are merely entries to that database.

To write data (in other words, assign $BTC balances to an address) into this decentralized database, there needs to exist some kind of foolproof mechanism that governs this function (if not, people could just write $BTC to themselves at will). This mechanism must be free of human interference, such that there exists no room for opportunistic behaviour to skew incentives. To satisfy all the above criteria, Satoshi Nakamoto (aka the pseudonymous creator of Bitcoin) came up with what we now know as proof-of-work.

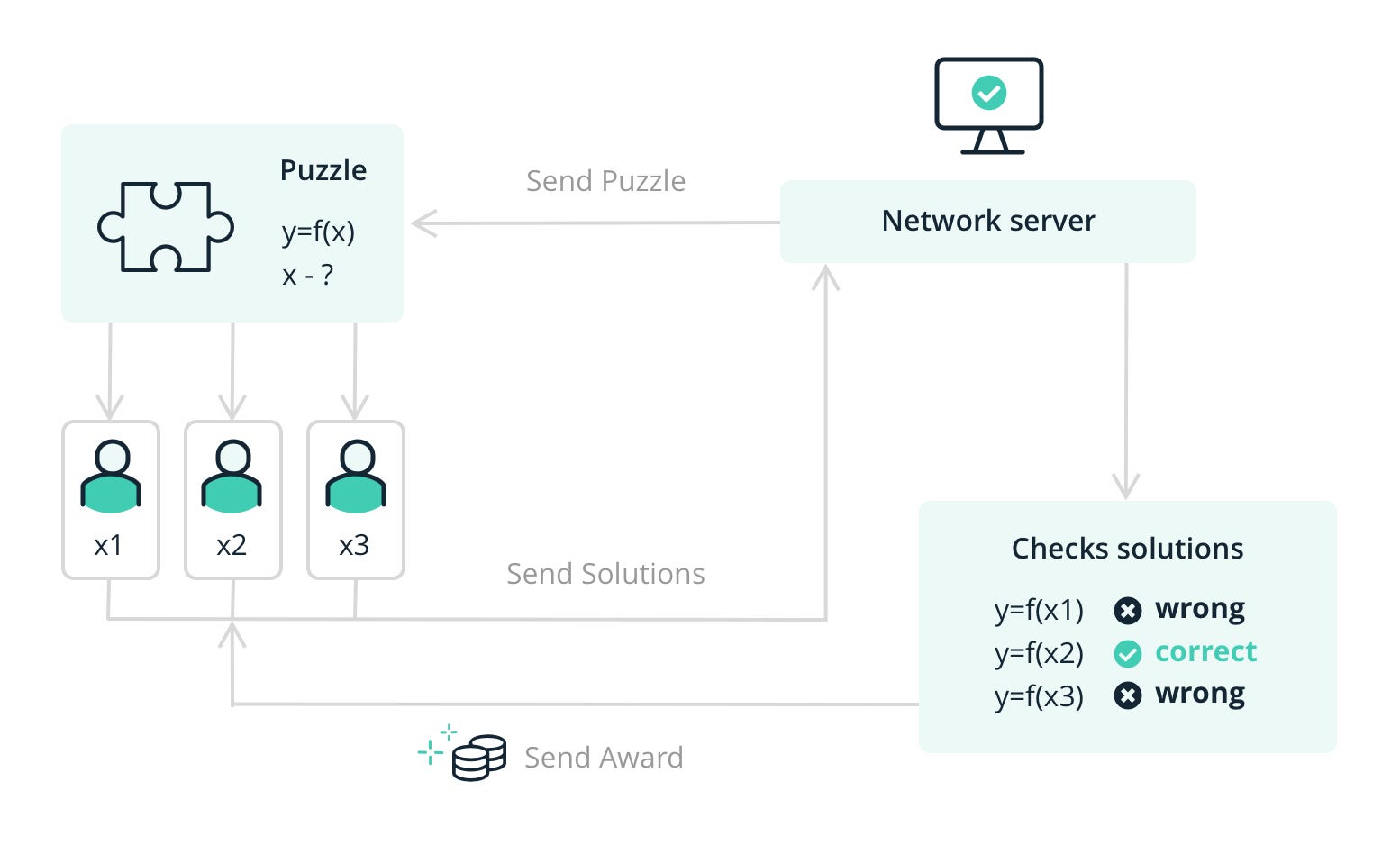

In simplest terms, proof-of-work pits “miners” (a term referring to anyone maintaining the Bitcoin database) together into a “math competition”, where the fastest computer to solve the mathematical problem gets to write data into the database.

This competition occurs on every block time, meaning that for each block (the “row”) that gets appended into the blockchain (the “database”), there exists an “evaluation period” (the “block time”) in which the host of the math competition can adjust the difficulty level of questions on the next round based on how well or terrible the computers have performed on the previous round.

The target benchmark is 10 mins for Bitcoin, meaning that if a computer can solve the question below the 10-min mark, the difficulty will be adjusted upwards in proportion to how much faster the computer is relative to this 10-min mark (and vice versa).

Since people get rewarded in $BTC when their computers are the first ones to solve the math puzzle, they are incentivized to procure more and more powerful computers in a bid to get more $BTC, which in turn triggers the Bitcoin network to adjust its difficulty further up, which then spurs people to obtain even more powerful computers.

This race-to-the-bottom is essentially the root cause of Bitcoin’s huge carbon footprint. In theory, if people stop procuring more powerful computers in a quest to outcompete each other, then Bitcoin’s energy use can be brought down to the tiniest of levels. But this is wishful thinking at best: as long as there are outsized incentives to be won for a select economic actor over the others, then competition will always exist by default.

Bitcoin = Crypto; Crypto ≠ Bitcoin

Make no mistake, Bitcoin is by far the largest cryptocurrency by market cap. However, it is not the only cryptocurrency out there. In fact, there exists thousands of cryptocurrencies, each with their own consensus (proof-of-work is Bitcoin’s consensus mechanism). Critics and proponents of Bitcoin can go at it all day on whether Bitcoin’s consensus mechanism justifies its utility — but it is simply unfair to drag other cryptocurrencies into the fray, considering the fact that they are running on a completely different consensus mechanism than Bitcoin’s proof-of-work.

One such cryptocurrency is Ethereum, currently the second-largest by market cap. Ethereum is a smart contract compatible blockchain, meaning that unlike Bitcoin which can only do simple send/receive transactions, applications can be developed on top of Ethereum to do more complex computations such as swapping tokens, lending/borrowing, minting NFTs, and other kinds of applications that we are not exposed to yet.

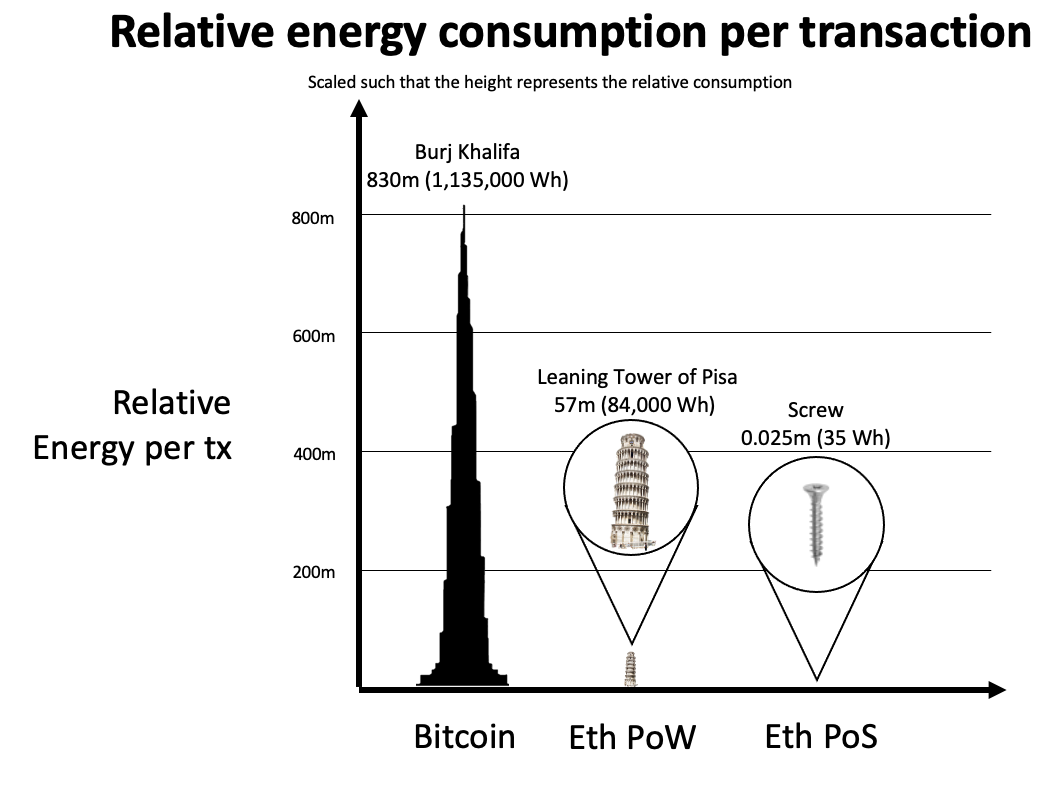

Just like Bitcoin, Ethereum’s consensus mechanism is currently proof-of-work — however, the Ethereum community is of the opinion that this mechanism is unsustainable in terms of its energy use and potential scalability, and as such has committed to transition towards a more energy-efficient consensus alternative called proof-of-stake.

The key distinction of proof-of-stake with proof-of-work is that instead of having miners compete for blocks, the network assigns blocks to miners based on their number of staked $ETH. The bigger a miner’s $ETH stake out of the network’s total staked $ETH, then the miner will have a higher chance for the right to write the next block into the blockchain. The absence of “math competitions” to determine consensus means that proof-of-stake by default will be significantly more energy-efficient than proof-of-work.

Indeed, “The Merge” is still in the works at the time of this writing. However, there are still plenty of other environmentally friendly blockchain networks that are already fully operational.

One such example is Fantom, where it uses a consensus mechanism called Lachesis PoS in a bid to further scale the Fantom network even more than ETH2.0. To achieve this, instead of using a “traditional” blockchain data structure for its decentralized ledger, they employ what we call as a DAG (directed acyclic graphs).

Another example of a scalable and energy-efficient cryptocurrency is Solana. They are highly touted as the world’s most performant blockchain, which is achieved through its so-called seven core innovations, spearheaded by its proprietary Proof of History PoS consensus mechanism.

Heck, there is even a carbon-negative blockchain network (at least according to its transparency reports). Celo, a mobile-first blockchain network with Valora as its flagship product, achieves its carbon-negative goal through a combination of its already energy-efficient blockchain along with its “Carbon Offsetting Fund”, which basically sets aside a fraction of the rewards that is meant for Celo validators in favor of donating them to an organization that commits to using those assets for carbon offsetting projects.

No Size Fits All

It really doesn’t have to be one way or another. Pro-crypto doesn’t necessarily entail an anti-environment stance, nor that anti-crypto is pro-environment.

As such, no matter if you are a hardcore environmentalist with the belief that the most important consideration for a product or service is its carbon footprint irrespective of its utility, or a “decentralization maximalist” with the opinion that the superiority of Bitcoin’s proof-of-work renders its energy usage worth its weight in gold (this is an infamously contentious issue; for further reading: Blockworks’ take on proof-of-work vs. proof-of-stake), the plethora of cryptocurrencies ensures that there will exist communities that are aligned with your principles or the causes that you are advocating for.